It would take 5,350 miles to travel back to Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi, Ukraine, from Bristol, Tennessee, but it would take a time machine to travel back before the destruction, before the war.

Sophomore Alisa Moha knows this truth all too well. Two months ago, Moha and her immediate family left Ukraine, seeking refuge in the U.S.

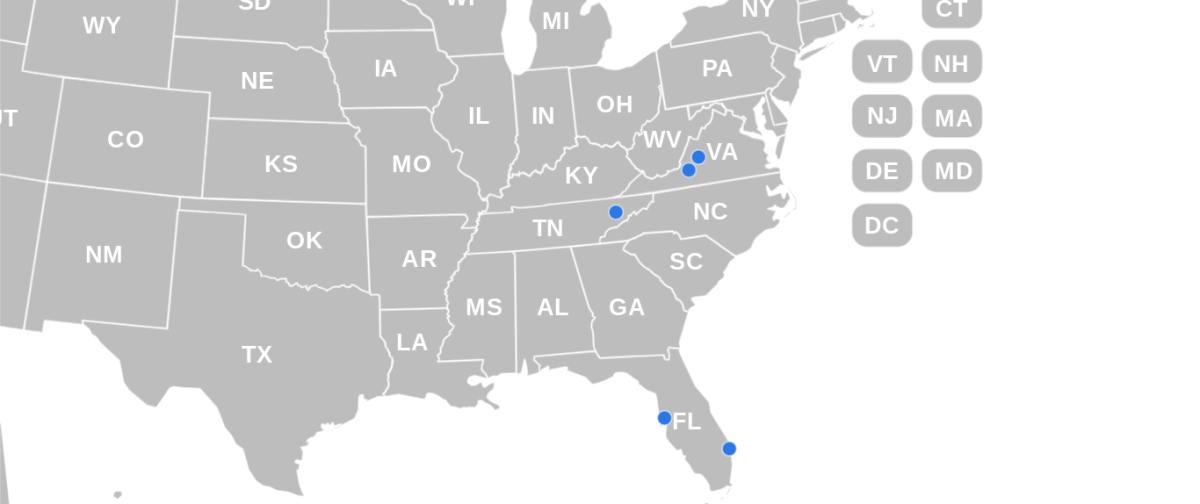

“My trip was very long,” Moha said. “It was about three days. I rode by bus to Romania; next, I took a plane to Vienna, and then I took a plane to the U.S.”

Upon arriving in the U.S., Moha states that everything seemed “strange” from the beds to the switches to the modes of transportation.

“Arriving in the U.S was like a breath of fresh air and the world seemed brighter after two years of living in a country at war,” Moha said.

Moha’s arrival in the U.S. was aided by family friends that they had known back in Ukraine, such as sophomore Nikita Mashkin, who also now attends Tennessee High.

“Our mothers met when they went on walks with us in strollers. Later, we went to the same kindergarten, and then to [the same] middle school together,” Moha said.

Moha and her family also found support at local churches, Central Presbyterian and Celebration Church. Here they met other Ukrainian families and individuals who were willing to help.

“People understand our struggles with language and I understand that the U.S. is a country of immigrants and is more supportive towards immigrants,” Moha said. “People [here] are so kind; they want to help you.”

For Moha, Bristol has provided her with a new home, and with that hope. The pieces of her new home have allowed her to reminisce about the memories she holds dearly.

Recently, as she strolled through the wooded trails of Steele Creek Park, Alisa experienced the transportive power of nature that enabled her to span that distance of space and time, and return home once again.

The smell of autumn leaves, Bristol’s leaves, helped her return to a memory when she was seven years old.

“We went to the forest [to collect] mushrooms with my parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents,” Moha said. “Great-grandmother told us her life stories; afterward my dad, brother, and I played ball. It was lots of fun and I appreciate this warm memory.”

While her actual hike took her through Bristol’s ash and sycamore, poplar and maple, her mind was thousands of miles away in a Ukrainian forest of the dark fields dotted with yellow mushrooms.

This thread of home, capable of washing away feelings of displacement, has continued through the taste of Ukrainian dishes, prepared stateside.

“I feel the smell and feel the taste [of food], and I can remember warm memories of my childhood from when my grandma cooked these dishes for me,” Moha said. “I think [this makes] food an important piece in my family.”

The nostalgia evoked from the smell of pies and happiness from the rich color of borscht, a soup made from red beets, brought her comfort during the hardest experiences of her life.

These memories are her fortress of hope, reminding her of who she is. The comfort of home may be unreachable, but, for now, it may be attainable through Moha’s memories.

Correction:

Oct. 18, 2024

An earlier version of the Ukranian translation for this story erroneously referred to Alisha Moha as “Алісі Могa.” In the context of the sentence, the correct spelling is Алісі Могі. Similarly, an earlier version of the translators’ attributions incorrectly referred to her as “Аліса Муха” rather than the correct spelling: Аліса Мога.