185 years ago, in the depths of economic calamity, the United States called its esteemed hero of the War of 1812 out of retirement to serve in the nation’s highest office.

William Henry Harrison, who had spent the decade prior in private, achieved a landslide mandate to change the country from its Jacksonian ways. However, less than a month into his administration, Harrison fell to a fatal illness, making his presidency the shortest in history, and his agenda was never realized.

Born as the youngest child of Founding Father Benjamin Harrison V in 1773, Harrison would refer to himself as a “child of the Revolution” for the duration of his life. He lived just thirty miles from the Battle of Yorktown, and after independence, his father served as governor of Virginia; his older brother, Carter, served in the US House of Representatives.

After his father’s death in 1791, Harrison was encouraged by Virginia Governor Henry Lee III to begin a military career. He initially fought in the Northwest Indian War and was promoted to lieutenant in 1792. Helping secure the nation’s victory in the war, Harrison resigned from the military in 1798 with the rank of captain.

The same year he left the Army, Secretary of State Timothy Pickering, a friend of Harrison, influenced President John Adams to appoint him as governor of the Northwest Territory. In the role, Harrison worked to decrease the cost of land in his territory as westward expansion loomed.

In 1799, Harrison’s constituents elected him as a non-voting delegate to the House of Representatives, and in the House, he helped to pass the Land Act of 1800, making it easier for citizens to acquire property.

After the Federalists’ defeat in the 1800 elections, John Adams appointed Harrison as the first governor of the Indiana territory during his final months in office. In Indiana, Harrison made western expansion his top priority.

After being granted expanded authority in 1803, Harrison signed numerous treaties with Native Americans limiting the amount of territory they controlled.

Despite Harrison’s expansionist success, his pro-slavery position conflicted with many abolitionists in the territory. The territorial legislature repealed many of Harrison’s pro-slavery acts and moved towards statehood.

In 1810, Shawnee leader Tecumseh organized many natives in opposition to American expansionism. Harrison was concerned that Tecumseh’s actions would threaten Indiana’s bid for statehood, so he took command of a military force and moved north.

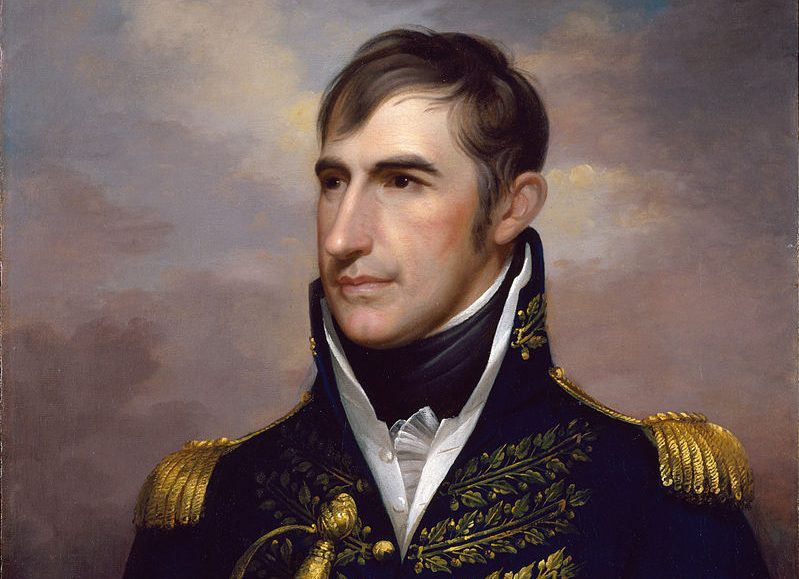

Once his troops encountered the natives, Tecumseh’s force was easily defeated, and the event came to be known as the Battle of Tippecanoe. Harrison’s actions in the battle brought him national acclaim and status as an American hero.

Once the War of 1812 began, Harrison resigned his governorship and was appointed a major general in the Army. He was made commander of the Army of the Northwest, and after General James Winchester led an American defeat at the Battle of Detroit, Harrison was promoted to Winchester’s former position.

After fortifying and reinforcing his position, Harrison launched an invasion that recaptured Detroit and moved into Upper Canada. The invasion was held off by British troops, but in the battle, Colonel and future Vice President Richard Mentor Johnson killed Tecumseh—an incredibly popular action that boosted both Harrison’s and Johnson’s national reputation.

Following the end of the war, Harrison settled in Ohio and was elected to the House of Representatives, serving from 1816 to 1819. President James Monroe declined to appoint Harrison to the role of secretary of war or minister to Russia when he became president in 1817, which disappointed Harrison.

During the Monroe presidency, Harrison was elected to the Ohio Senate, but lost elections for governor, a seat in the House, and a Senate seat.

However, at the end of the Monroe Administration, Harrison was elected Senator, and four years later, President John Quincy Adams promoted him to minister to Gran Colombia in his final weeks in office, finally satisfying Harrison’s desire for a federal position. However, Adams’ successor, President Andrew Jackson, did not retain Harrison. He returned to his Ohio farm, lacking considerable wealth.

Out of office for the first time since the 1810s, Harrison prioritized the maintenance of his family farm. As he only made a small military pension, he and his family lacked significant wealth. He briefly opened a distillery in an attempt to make money, but he shut it down after his sales induced widespread public drunkeness.

Despite his lack of stature at his Ohio home, eastern political bosses believed that his status as a military hero would make him advantageous as a prospective presidential candidate. As he had previously been an ally of John Quincy Adams and an opponent of Andrew Jackson, he was primarily courted by the anti-Jacksonian Whig Party and its leader, Senator Henry Clay of Kentcky.

In 1836, the party informally nominated Harrison as one of its four candidates for president. The party’s strategy was to nominate four regional candidates with the hope of preventing Democratic Vice President Martin Van Buren from achieving a national electoral majority.

Harrison was on the ballot across the non-slave holding states and won 73 electoral votes. The party strategy failed, however, as Martin Van Buren was elected president with a majority of 22.

Right as Van Buren’s administration began, a financial crisis brought the nation to a standstill. Many blamed the recession on the economic policies of Andrew Jackson, and Vice President Van Buren had been a staunch supporter and protégé of the president throughout his entire career.

Jackson had dedicated much of his presidency to dismantling the Second Bank of the United States and slashing government spending, and his doctrine became the target of many embattled citizens.

In the face of extreme Democratic unpopularity, the Whigs abandoned their regional strategy and instead opted to run one single candidate. At the party’s national convention in late 1839, Harrison, General Winfield Scott, and Henry Clay were all candidates for the presidential nomination.

Clay initially led Harrison in balloting, with Scott in a distant third place. The convention had a unique voting system, in which each state pledged all of their delegates to one single candidate, rather than allowing each delegate to vote for themselves.

This worked against Clay’s national strategy, and through the support of many populus Northern states, Harrison clinched the nomination on the fifth ballot.

However, little thought was given to the vice presidential nomination. As Clay, a Southerner, was the presumptive presidential nominee before the convention, many Northern vice presidential candidates believed that they had a good chance of being nominated for the purpose of regional balance. However, with the unexpected nomination of Harrison, a Northerner, very few Southern candidates had previously prepared to seek the vice presidency.

Major figures such as John J. Crittenden, John Bell, and Willie Person Mangum declined to run for vice president, leaving an even bigger void at the position. However, John Tyler, a former Democrat who once served Virginia as governor and senator, stepped forward as a candidate. Tyler had previously been a faithful supporter of Henry Clay, and was therefore palatable to his wing of the party. He was nominated unanimously on the first ballot.

In the general election campaign, Harrison emphasized his frontier roots in contrast to Martin Van Buren, who resided in New York. His slogan, “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too,” became nationally famous.

Moreover, campaign advertisements portrayed Harrison as “the log cabin and hard cider candidate,” further bolstering his populist image. In contrast, Van Buren’s campaign referenced Harrison’s age, labeling him a “granny.” In light of that criticism, Harrison pledged to be a one-term president.

Despite the efforts of its leaders, the Democratic Party largely failed to rectify its poor economic reputation, and Vice President Richard Mentor Johnson’s previous slave affairs brought scandal to the race.

That fall, Harrison won in an electoral landslide victory against Van Buren, and the work of forming his administration began.

Despite the party platform’s opposition to political patronage, Henry Clay sought to fill the government with reliable Whigs. He attempted to dictate almost every federal appointment to the president–elect, but Harrison rebuffed.

“Mr. Clay, you forget that I am the president,” he said.

Harrison escalated the situation by naming Daniel Webster, one of Clay’s arch-rivals, as secretary of state. His sole concession to Clay’s interest was appointing his protégé, John J. Crittenden, as attorney general. Past the ambitions of Clay, countless office-seekers came to Harrison requesting appointments during his transition period.

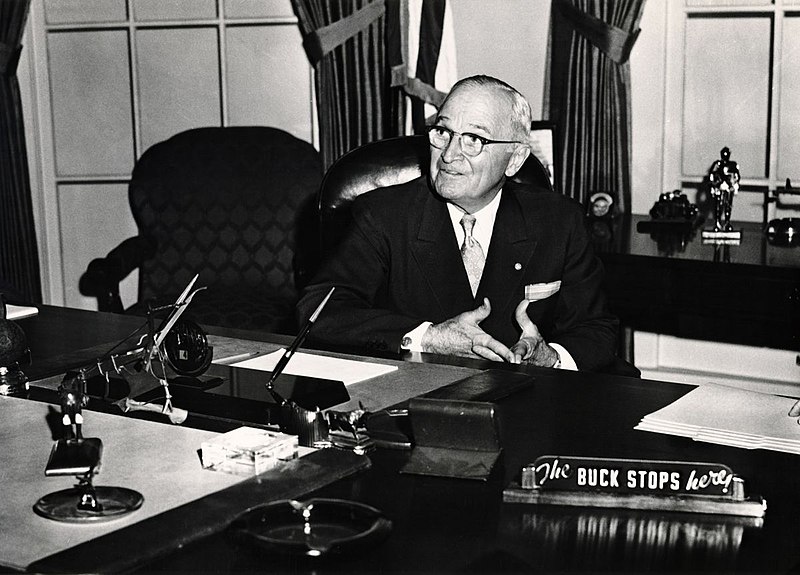

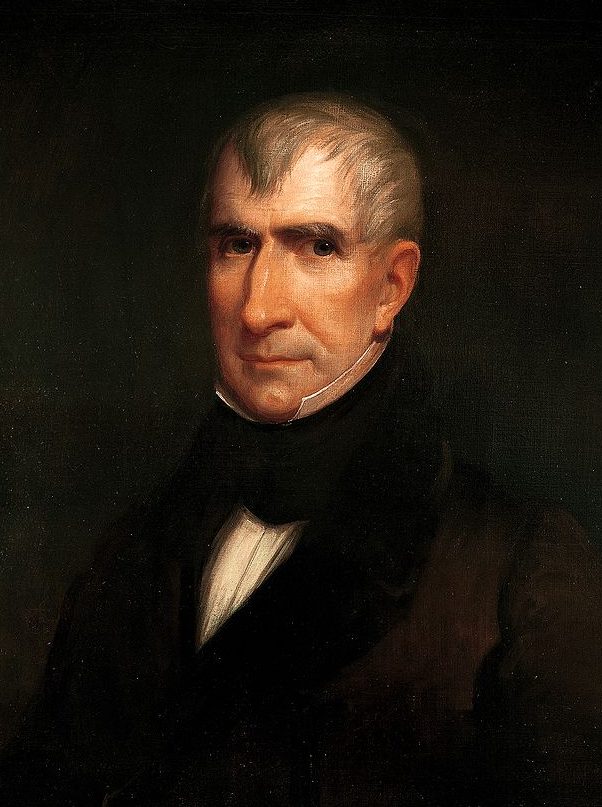

As Harrison finally assumed the presidency on March 4, 1841, in the cold rain, he delivered the longest inaugural address in American history. At nearly eight and a half thousand words, it took him close to two hours to deliver.

He wrote the entire speech himself, although it was edited by Webster. He pledged not to personally interfere with Congressional decisions—-something Andrew Jackson was infamous for—and he instead made general statements on the tone of both his presidency and the nation.

Shortly afterward, Harrison entered the Executive Mansion and began the work of his presidency. His animosity with Henry Clay continued, as he refused to fire all Democrats from the government and called a special session of Congress, both of which Clay had reservations regarding.

His relationship with Clay came to be so strained that Harrison ordered him to never enter the Executive Mansion again and address him only in writing.

On March 24, Harrison took his daily walk through the local markets, fatefully choosing not to wear a coat in the wet conditions.. He also declined to change clothes when his commute was complete, and he fell ill shortly thereafter.

A horrific fever developed, and his doctors attempted bloodletting. Their efforts proved to have a negative effect as he was quickly diagnosed with pneumonia.

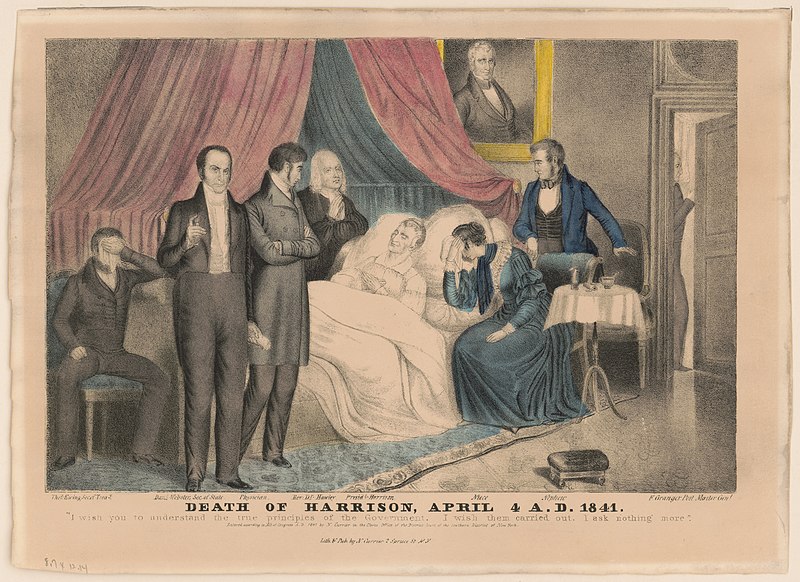

On the evening of April 3, Harrison suffered from painful bowel movements and became delirious. He delivered his final words to a nearby doctor, which were assumed to be intended for Vice President John Tyler.

He died shortly after midnight, and a constitutional crisis ensued. Many believed that Tyler was only to serve as acting president until a special election to replace Harrison, but Tyler disagreed. He insisted on taking the oath of office and officially becoming the tenth president of the United States, and Congress contentiously ratified his actions later that year.

Harrison’s death and Tyler’s accession set a precedent that would last for all of American history, and would officially become law by virtue of the 25th Amendment to the Constitution in 1967.

During his administration, Tyler would forgo the doctrines of both Harrison and Clay and became a political maverick, abandoned by both the Democrats and the Whigs. He set the nation on course for Manifest Destiny, which was further bolstered by his successor, James K. Polk, who Clay would go on to lose the 1844 election to.

Despite being once acclaimed as an “American hero,” Harrison’s political significance has been greatly forgotten by the American people, largely because his death began an infamous plague that haunted American presidents for 122 years.

According to legend, Shawnee Prophet Tenskwatawa laid a curse upon Harrison at the Battle of the Thames as retribution for the land he had seized and natives he had killed.

“Harrison will die I tell you, and after him, every great chief chosen 20 years thereafter will die,” Tenskwatawa allegedly said. “And when each one dies, let everyone remember the death of my people.”

Tenskwatawa’s prediction proved true, as every president elected in a year ending in zero died in office until 1981, when President Ronald Reagan narrowly survived an assassination attempt. The curse appears to be broken, as no presidents have died in office since John F. Kennedy.

In terms of actual policy, Harrison had a great chance to change the future of America, with many “what-ifs” being connected to his name.

He could have approved the national bank, greatly changing the American economy, he could have taken measures to slow westward expansion, and he could have moved the Whig Party out of Clay’s control.

Yet, Harrison was unable to do any of these things in the mere thirty days he spent in office. Harrison became forgotten because, in the span of a month, he lacked the opportunities to do anything memorable.

Death stripped away the promise of Harrison’s vision, and due to the poor healthcare of the time, it was allowed to wipe his name and his ambition from the minds of his countrymen.

Note:

Aiden Smith was not editor-in-chief at the time of this article’s publication. Rather, he was news editor and political correspondent. At the time, Hayden Arnett was editor-in-chief.