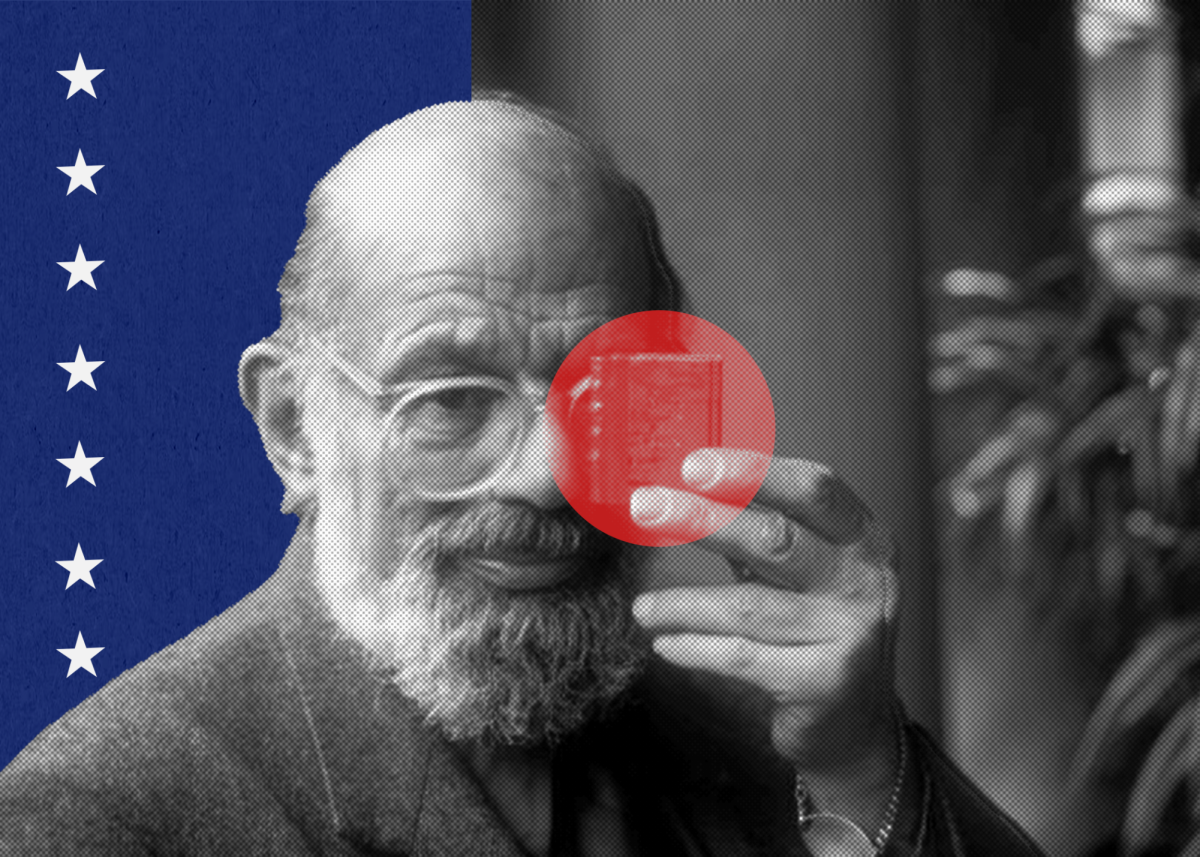

Reading Allen Ginsberg is akin to experiencing a spiritual awakening on a random Tuesday morning in the month of November—it’s frosty, it’s sinister, and it’s so American.

Though his masterpiece is often hailed to be “Howl,” his truth, his gospel, is titled “America” after the country that spit him out and raised him.

The opening line, “America I’ve given you all and now I’m nothing,” almost needs to be separated in two parts to gauge the rhythm of the poem: “[America][I’ve given you all and now I’m nothing].”

Within Ginsberg’s language, America becomes an entity. America is a person tormenting Ginsberg whilst also remaining just an idea. America took everything from him.

Like so many people chasing the American dream, “America” becomes incredibly relatable when people look at their own life. Even just as students, people give so much of themselves just to have it spit right back at them.

Bringing up issues of obsession, false journalism, libraries full of tears, the privilege of beauty, and the cold war being waged more between Americans than America versus Russia, Ginsberg does more with his “mystical visions” than the politicians that failed him.

He speaks like a child and then like a sage, like a man of Berkley, a then a man of America. He speaks like a man of the sixties fed up with his country.

Just like the opening line, nearly every sentence is either directly addressing America or the ideals of American people until Ginsberg says, “I’m addressing you,” directly referring to the audience.

This shatters the perspective of the poem, breaking Ginsberg into reality. With this three-word sentence, Ginsberg reminds his reader that he is talking to them about them.

Then Ginsberg goes back informing himself that, “[he is] America. [he is] talking to [himself] again.” Nobody is listening to Ginsberg and nobody cares what he has to say.

America has become Ginsberg at this point in the poem, as he speaks of how troubled and uncaring he is, until he remembers “[he] is a Catholic,” and can never lead America—he can’t be America being who he is.

Once again, he becomes human, reciting about becoming holy, preaching peace, removing the human war. While bringing up war and conspiracy in a paranoid manner, Ginsberg mocks the idea of racism and fear of man’s destruction.

Ginsberg then brings an end to this paranoia by claiming that he should fight—that we should fight as a country—and emphasizes that he can’t even join the army to fight.

As a nearsighted, “psychopathic” man, he decides to put “[his] queer shoulder to the wheel,” to fight for America.

Yet, he can not fight because of the political differences going on at the time and because of his “queer shoulder”—a reference to both not allowing queer men into the army at the time and those with mental health struggles.

Yet, Ginsberg’s magnum opus is legit as a fighting piece because he stands for what he believes in through his verse, through his rambled reasons.

“America” by Allen Ginsberg is legitimate literature due to his plight of struggle depicting American Life in a way that’s just as revealing as classic American painter, Norman Rockwell’s, illustrations of common life at the time.

Ginsberg tells his story of America while “refusing to give up [his] obsession,” just as he refuses to give his hope for the future of the nation even asking America, “is this correct?”

Stepping away from the poem, a gentle idea of change is brought on. A true writer from the 1960s, Ginsberg leaves his readers with a young revelation towards America: “[they’ll give] it all and [then be] nothing…[ he’s] not sorry.”

Amy Marie | Dec 12, 2024 at 12:41 PM

neat