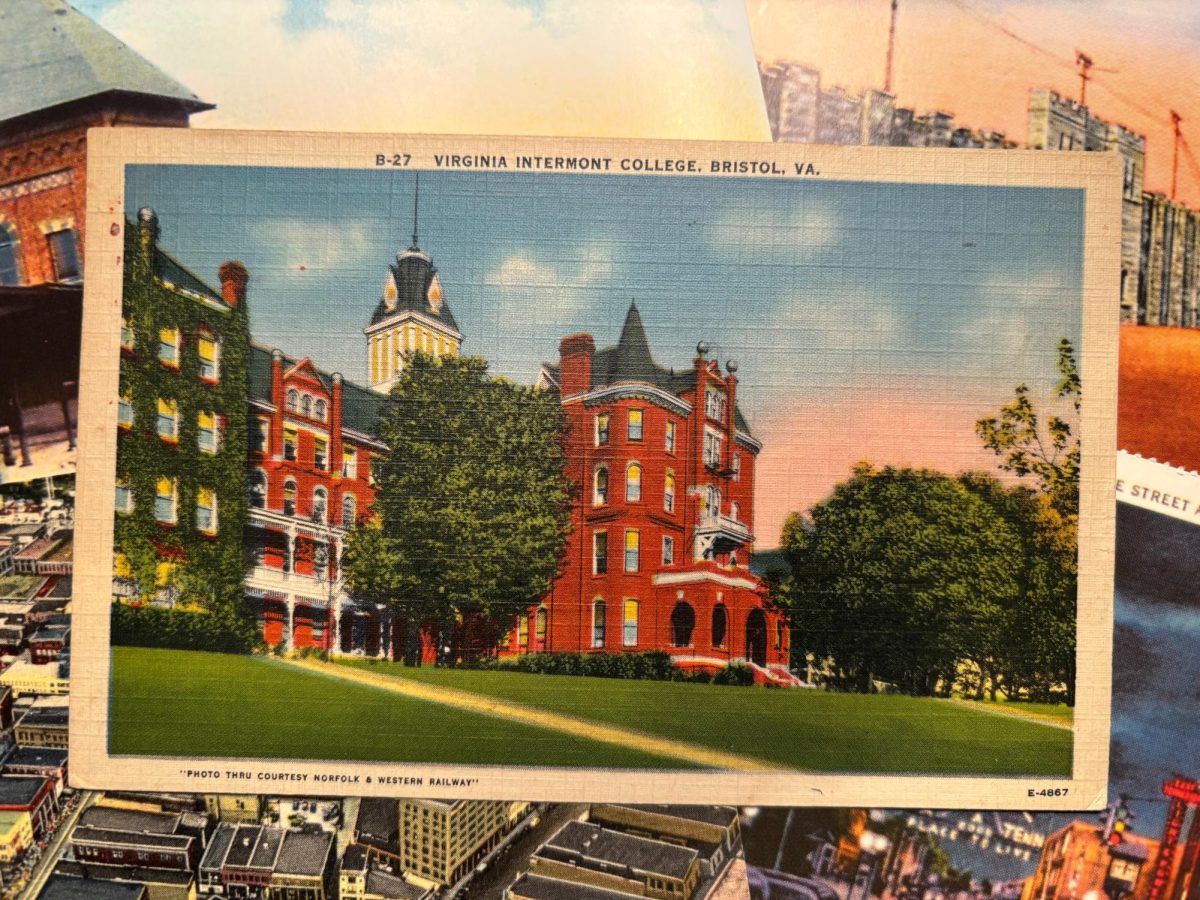

Blaring sirens pierced the cold fall morning as firetrucks flew down the avenues of Bristol, Virginia: a city landmark was in flames. A little past 12:00 a.m. on Dec. 20, 2024, a large fire was reported on the former Virginia Intermont College campus. Unbeknownst to onlookers, the expanse of this tragedy was the creation of an unhealable scar.

Virginia Intermont College, often referred to as VI, was founded in 1884 under the name of the Southwest Virginia Institute. For the first nine years of operation, the campus was located in Glade Spring, Virginia, about 25 miles from its more well-known placement.

The school was established by Reverend J.R. Harrison, a Baptist minister, in hopes of bringing higher education to women of the region. In Virginia, higher education had already been made available to women, but it was limited to only the wealthy, who could afford the high admission costs of the private institutions.

More notable than VI, the State Female Normal School opened in Farmville, Virginia, in the same year. It was the first public college for women in the state and set a new precedent for this access to education.

It came as a part of public institutions across the state that offered women the right to affordable education. These schools were placed around the state to serve the main geographic regions.

The Southwest Virginia Institute, however, was a private institution.

During this time in Glade Spring, the Southwest Virginia Institute grew at such a rate that the college was required to move to a larger campus. This transition started in 1891 and the relocation was completed in 1893 when classes started that September. The new location became the prominent hill in Bristol, Virginia.

Not long after the opening of the new site, the school experienced its first name change. Then known as the Virginia Institute, the college found itself at the turn of the century. This name, however, did not last far into the 1900s.

In 1908, the institute received its second and final name change. The name that is now synonymous with the campus was cemented: Virginia Intermont College.

Two years later, the college readdressed its curriculum and reorganized its structure. This change brought the school into the junior college movement and resulted in an accreditation from the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools.

This was a major achievement for VI, as they were the first two-year school to receive this acknowledgment.

Virginia Intermont College, a recognized learning institution at this point, saw successful growth and expanded with five new buildings in the 1960s. This was just before the school witnessed a major shift.

In 1972, VI became coeducational and started offering four-year programs. This advancement led to the creation of a larger scope of students who could attend and fulfill their educational desires at the institution.

With standardized operation for the following decades, the school saw few major changes or events on the campus. However, with an increasing number of students, the institution reached its peak enrollment of just over 1,100 students in 2004.

Nonetheless, with a relatively low enrollment compared to other colleges, classes were small and students had the ability to grow closer to their professors and peers.

“I enjoyed learning from the professors there and getting to know some of the students, especially the international ones,” said Class of 2003 graduate Tammy Nichols.

The connections between students became a large part of attending Virginia Intermont College.

“VI was a close community and it felt like home,” said Amber McMurray, an alum who also graduated in 2003.

During this time, sports acted as a great attraction for students. Specifically, the school’s soccer team brought students from all over the world to Bristol.

But by 2008, the college started to face enrollment and financial problems. In just four years, the school’s enrollment decreased by over half of what it was.

In 2007, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools placed a warning over Virginia Intermont College due to the financial situation of the school. These concerns, however, were resolved by 2009.

The SACS placed VI on warning again in 2010. The commission held concerns of the financial viability, as before, and this strung into 2011. They raised the status of VI to a more serious probation in late 2012.

But with little change this time, the SACS removed VI from membership in June of 2013. An appeal was put in place, but it failed in August. This challenge led to a lawsuit that was taken to Georgia federal court. As a result, the accreditation was still in place temporarily.

This accreditation is important for a college, as it is what allows them to offer federal financial aid. Additionally, it guarantees that they meet basic standards of quality for students.

Beyond a fight for accreditation, financial issues based on the struggling post-recession economy left a weight on the school. By this point, there were only 378 students attending in 2013.

At the same time as the warnings by the SACS, the first female president, Dr. E. Clorisa Phillips, was hired. This achievement, something past due given the original principle of a women’s college, came about in July of 2010.

Phillips came from a background of thirty years in an administrative position at the University of Virginia. Now as the head of the smaller college, she started fundraising initiatives that would go to support projects such as renovations and improvements to the historic campus.

Along with this, her fundraising efforts would go to build new academic and athletic programs. These came into effect during the 2012-13 academic year.

Despite her efforts, the school continued to face decreasing enrollment. In hopes of improving the rising issues, VI announced plans to merge with Webber International University in January of 2014.

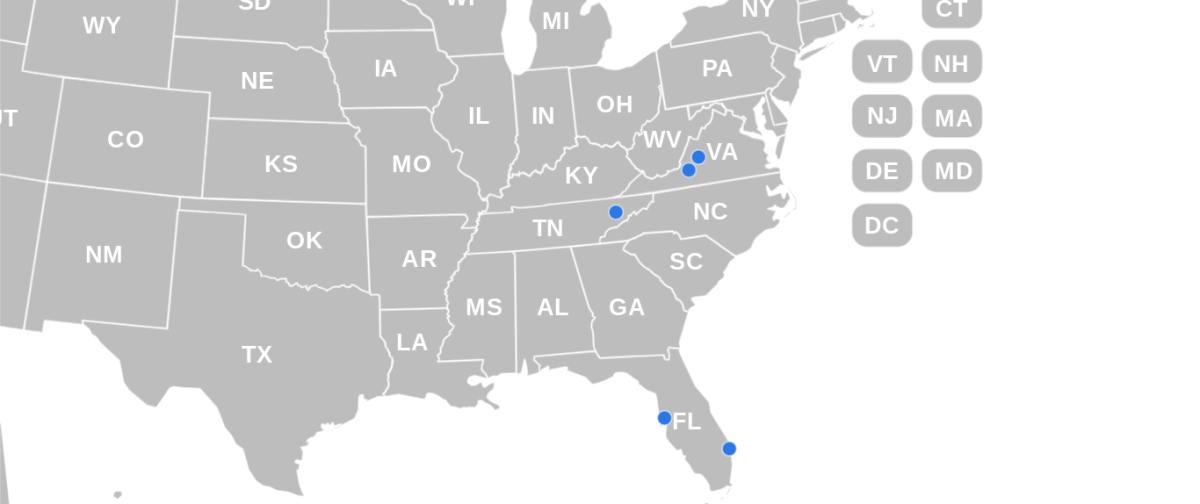

The school had been looking into a form of merger after they lost their accreditation by the SACS. Webber International University, a private college in Babson Park, Florida, was able to form an agreement with VI.

Webber is an independent university in central Florida. The school is renowned for its business program in which it offers both bachelor’s and master’s degrees.

The plan with Virginia Intermont would not have been the institution’s first merger. There is a second branch in Laurinburg, NC, which is the result of a merger with the former St. Andrew Presbyterian College in 2011. The result is St. Andrews University.

The plan, however, was at the mercy of the many organizations and departments that it had to go through. To materialize completely, the merger needed to get approval from SACS, the U.S. Department of Education, and the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia.

Just months later in April, it was announced that the plans for the merger fell through. This raised many concerns for the future of the school, for as of July of that year, the school would lose its temporary accreditation.

Phillips, however, assured that the lack of accreditation would not affect the operation of the institution; they still had the number one priority of the students. She stated that it was up to the school to make important judgments about the future of the college, but there were no decisions made.

At this time, there were only 320 students attending the school, and about a third of them were going to graduate on May 4 of that year.

Local leaders, during the time before the graduation, worked to find a solution to save the failing institution. However, the continuous problems became evident in the school’s announcement of canceling the next athletics season.

By this point, VI was being threatened by the city for their lack of ability to pay their utility bills. If they failed to pay them, the utility lines would be turned off, acting as another testament to the struggles of the college.

During the graduation ceremony, the faculty president of VI, Dr. Robert Rainwater, announced that the institution would be closing its doors. After 130 years of education, Virginia Intermont College would no longer be offering classes.

The next day, Phillips’ resignation was accepted by the board of trustees, an action taken due to personal reasons. She worked as the head of the school for 4 years and led many efforts to revive the institution, but none of them were successful enough to restore it to its former state.

In reflection of the event, alum Joshua McMurray said, “I felt like I [lost] a lot of money because now my credentials [have] no backing.”

Nichols, however, viewed the closing less as a blow to her degree, but to the community and her memories.

“I was not surprised to hear that it closed because when I was there, it was rumored that they had financial problems, [but] it was sad due to having fond memories of my time there.” Nichols said.

However, this was just the start of extensive turmoil and uncertain situations that would go on for years, plaguing the campus.